Shell Scripting Part 2: Accepting Inputs and Performing Shell Arithmetic

Hi! This article is the second part of the Howtoforge shell scripting tutorial series. By this time, I assume that you have read the first part of the series and know how to create a simple script and execute it. In the second part, you will learn how accept inputs from the user and process them through shell scripting. Let's get started!

Variables in Linux

Just like programming languages, Linux shell has the capability of storing data in variables. A variable is a container that temporarily stores data that will be processed through a programming language. There are two types of variables in Linux: the environment variables and shell variables.

Environment Variables

The environment variables are the default variables in Linux and are used to pass information across processes in the shell. Environment variables are case-sensitive and should be always capitalized in order to access them.

The table below shows the common environment variables in Linux shell:

| Variable name | Usage |

| BASH | Holds the full path of the command interpreter for Bash scripts |

| BASH_VERSION | Holds the bash release version of the machine currently used |

| HOME | Holds the relative path of the home directory. |

| LOGNAME | Holds the account name of the current user logged-in |

| OSTYPE | Holds a string that describes the current OS of the machine used |

| PATH | Holds a colon-separated absolute path of the executable files in Linux |

| PWD | Holds the current working directory of the shell |

| SHELL | Holds the preferred command line shell |

| USER | Works similar to LOGNAME. It holds the account name of the user currently logged-in |

| _ | Holds the name of the recently used command in the shell |

To display the value of a environment variable, the user has to prepend a dollar-sign ($) to the variable to be accessed. For example, to display some system information like the current working directory, logged-in user and the OS type using echo we use:

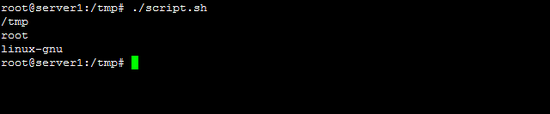

#!/bin/bash

echo $PWD

echo $LOGNAME

echo $OSTYPE

The result is:

To get the entire list of environment variables in Linux use the env command.

Changing values of environment variables

To provide system flexibility, these environment variables can be manipulated. To set a value to an environment variable, use an assignment expression (equal sign).

Example:

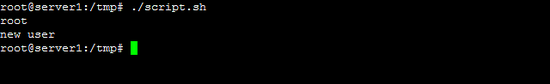

#!/bin/bash

echo $USER

USER="new user"

echo $USER

The result of the script is:

When you run the script, at first, the $USER in the line echo $USER shows the value of the USER variable. By using an assignment operator (=) the USER variable changes its value. However, if the user will assign unknown values to an environment variable, the shell will create another shell variable similar to the environment variable in the local context of the script but it will not affect the behaviour of other applications. Meaning, once our script will be closed, the USER variable will retain its default value.

Note that in our previous example, we omit the dollar sign ($) in the variable name when manipulating values of the environment variables such as the line USER="new user". Also, when using the assignment operator, there must be no space in between the USER and = sign. Adding a space between them creates an error.

Shell Variables

The shell also allows the user to declare variables. Just like PHP, to declare a variable in shell scripts, the user doesn't have to worry about declaring its datatype; the interpreter will automatically detect the variable's datatype based on the data that the user stores into it during runtime.

Rules in naming shell variables

Just like any programming language, there are rules in naming shell variables. The following summarizes the rules:

- The names of variables must begin with a letter or an underscore.

- It must only contain an alphanumeroc characters or an underscore.

- Variables are case-sensitive thus, the variables path, PATH and Path are different.

To prove this rule, we will create a simple script below:

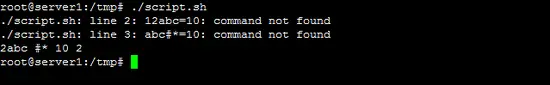

#!/bin/bash

12abc=10

abc#*=10

_abc=10

_ABC=2

echo $12abc $abc#* $_abc $_ABC

The lines 2 and 3 return "command not found" error because the variable 12abc begins with a numeric character and the variable abc#* contains illegal characters. We also proved that the _abc and _ABC are different variables and the line _ABC=2 do not override the value of _abc.

Assigning values to shell variables using read command:

read is a command that allows accepting inputs from the user. The syntax in using read command is:

read <variable_name>

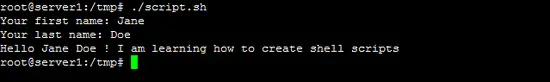

For example, we will create a script that will allow a user to enter his first and last names and display them. To let the user know what to do, we show a user prompt with the echo command.

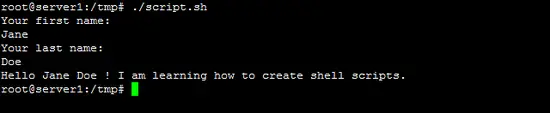

#!/bin/bash

echo "Your first name: "

read fname

echo "Your last name:"

read lname

echo "Hello $fname $lname ! I am learning how to create shell scripts."

The result is:

Please note that like in our previous example, we do not have to declare a variable in order to use it. The interpreter also automatically creates the variable that is used in read command. However, in the example, we repeatedly used echo command to create a prompt to the user. The read command has also the capability of creating a prompt while accepting user inputs. The syntax of using prompt in the read command is:

read -p "Your prompt: " <variable_name>

To simplify our previous code we can reconstruct the code to:

#!/bin/bash

read -p "Your first name: " fname

read -p "Your last name: " lname

echo "Hello $fname $lname ! I am learning how to create shell scripts"

Another benefit of the read command is that the command prompt is right after the text and not in the line below.

The read command can also be used to accept passwords. Unlike ordinary inputs, passwords are masked to provide security. The syntax in accepting a password is:

read -s -p "your prompt" <variable_name>

Performing simple arithmetics using the shell

Aside from accepting inputs and displaying output, the bash shell also has a builtin arithmetic option. The table below summarizes the builtin arithmetic operators of the Bash shell.

| Operator | Description | Syntax | Usage |

| + | Addition | a=$((b+c)) | Adds the value of b and c and stores it to variable a |

| - | Subtraction | a=$((b-c)) | Subtracts the value of c from b and stores it to variable a |

| * | Multiplication | a=$((b*c)) | Multiplies the value of b and c and stores it to variable a |

| / | Division | a=$((b/c)) | Divides the value of b by c and stores it to the variable a |

| % | Modulus | a=$((b%c)) | Performs modulo division of b and c and stores it to variable a |

| ++ | Pre-increment | $((++aa)) | Increments the value of variable a immediately |

| ++ | Post-increment | $((a++)) | Increments the value of variable a and reflect changes to the next line |

| -- | Pre-decrement | $((--a)) | Decrements the value of variable a immediately |

| -- | Post-decrement | $((a--)) | Decrements the value of variable a and reflect changes to the next line |

| ** | Exponentiation | $((a**2)) | Raise the value of a to the exponent of 2 |

| += | Plus equal | $((a+=b)) | Adds the value of a and b and stores it to the variable a |

| -= | Minus equal | $((a-=b)) | Subtracts the value of b from a and stores it to the variable a |

| *= | Times equal | $((a*=b)) | Multiplies the value of a and b and stores it to variable a |

| /= | Slash equal | $((a/=b)) | Divides the value of a by b and stores it to the variable a |

| %= | Mod-equal | $((a%=b)) | Perform modulo division between a and b and stores it to variable a |

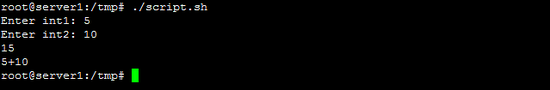

Note that every time you perform a arithmetic instruction, all of our variables will be enclosed with a dollar sign and double parenthesis. By doing this, the interpreter treats the values of our variables as integer numbers. Without it, the interpreter treats the values of the variable as a string. To have an example, see the script below:

#!/bin/bash

read -p "Enter int1: " a

read -p "Enter int2: " b

echo $((a+b))

c=$a+$b

echo $c

When we run our example, the line $((a+b)) adds the user's values that is stored in variables a and b respectively while the c=$a+$b treats variables a and b as string.

Conclusion

We have covered the how to accept inputs and store it on a variable and how to perform arithmetic operations in bash shell scripting. In the next part, we will feature control structures and particularly the decision structure.

References:

The Linux Information Project. (2007). Retrieved April 29, 2015, from Linfo.org: http://www.linfo.org/

Cooper, M. (n.d.). Advanced Bash Scripting Guide. Retrieved April 29, 2015, from http://www.tldp.org/LDP/abs/html/

Environment Variables. (n.d.). Retrieved April 29, 2015, from Ubuntu Documentation: https://help.ubuntu.com/community/EnvironmentVariables