The privacy implications of Windows 10 and its data collection have been a talking point since the operating system was released. And today, Microsoft published a response of sorts.

For the most part, the new blog post reiterates the company's (lengthy) privacy policy. Terry Myerson, leader of the Windows and Devices Group, describes three classes of data and describes Microsoft's approach to each.

First is the safety and reliability telemetry data, information about system and application crashes. Myerson says that this information should be anonymous; most of it has no personal information at all, and to the extent that personal information might be included (disclosed in, for example, file and directory names or fragments of memory included in crash reports), Microsoft tries to scrub all data that it receives.

The post also loosely describes why this information is useful: a third party graphics driver was recently found to be causing crashes. The telemetry data let Microsoft know that the crash was occurring and which driver was at fault, and it gave some hints as to what the bug was. Within 24 hours of finding the bug, a fix was rolled out to members of the Windows Insider program. Another 24 hours later and the fix was rolled out to all affected Windows users.

One of the major complaints about this telemetry data is that, unlike prior versions of the operating system where it was optional, most Windows users can't opt out in Windows 10. The Enterprise version allows crash telemetry to be disabled entirely. The mainstream Home and Pro versions, however, do not. Myerson's post is a little unclear on this point. He writes, "Our enterprise feature updates later this year will enable enterprise customers the option to disable this telemetry, but we strongly recommend against this."

We asked Microsoft what exactly this means, and the company said simply that the option to disable telemetry in the Enterprise edition will continue to exist. The ability to disable is not actually part of the feature update coming later in the year.

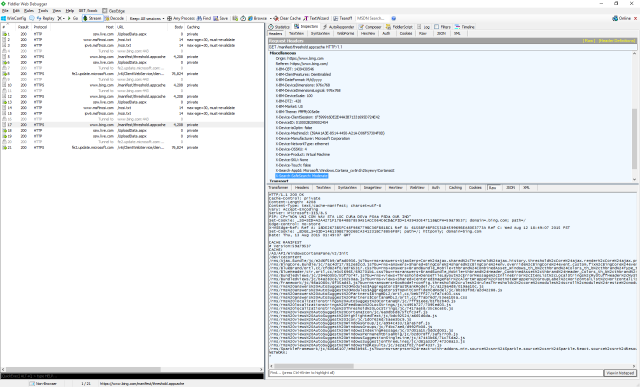

The second category is personalization data, the things Windows—and especially Cortana—knows regarding what your handwriting looks like, what your voice sounds like, which sports teams you follow, and so on. Nothing is changing here. Microsoft says that users are in control, but our own testing suggests that the situation is murkier. Even when set to use the most private settings, there is unexpected communication between Windows 10 and Microsoft. We continue to advocate settings that are both clearer and stricter in their effect.

Finally, Microsoft says that it doesn't use any personal data from e-mails or files to drive advertising. Left unspoken is the possibility that information from, for example, Cortana or store purchases or Bing searches all be used to target ads. This is clearly a jab at Google—it brings to mind the company's (thankfully abandoned) Scroogled campaign, which focused on Google's use of e-mail contents to target Gmail advertising. There's nothing new here and nothing that's likely to convince those concerned about Windows 10's privacy. Two classes of data are excluded—communications (including e-mail and Skype) and file contents—but everything else appears to be fair game for ad targeting. So while Cortana can't use your e-mail to tailor ads to your interests, it appears that she could use the appointments in your calendar to do so, for example.

In other words, the Windows 10 privacy situation is what Microsoft has always said it was. It collects a bunch of data, and while that data collection is generally justifiable—though not every Windows users will want every data-driven feature—opt-outs aren't always available, and it's not always clear how that data is actually used.

Nonetheless, there is a little progress. Windows has contained parental control features since Windows Vista. Accounts designated as being child accounts can be restricted and monitored in various ways, barring access to certain programs or certain kinds of website, for example. One feature that caused some complaints is that parents can receive weekly reports on their children's Internet activity. In response to this kind of feedback, including the feedback in the built-in app, Microsoft will be changing the parental monitoring feature to use "default settings designed to be more appropriate for teenagers, compared to younger children," and it is "working on ways to further enhance the notifications that kids and parents get about activity reporting in Windows."

Myerson's concluding paragraphs are also notable, as they appear to elevate privacy concerns to have a comparable significance to security issues. He writes, "Like security, we are committed to following up on all reported issues, continuously probe our software with leading edge techniques, and proactively update supported devices with necessary updates." There's also a process for reporting privacy issues. If this means that, for example, Microsoft will stop sending unique IDs and hardware data of the kind our testing demonstrated, then this approach to privacy will certainly represent progress. But as things stand right now, the Windows 10 privacy situation is substantially unaltered, and the lack of clear guidance and transparency that has concerned people since day one will continue to cause concern.

Listing image by Ruth Suehle, opensource.com

reader comments

312