After nearly a year of protests from the information security industry, security researchers, and others, US officials have announced that they plan to re-negotiate regulations on the trade of tools related to "intrusion software." While it's potentially good news for information security, just how good the news is will depend largely on how much the Obama administration is willing to push back on the other 41 countries that are part of the agreement—especially after the US was key in getting regulations on intrusion software onto the table in the first place.

The rules were negotiated through the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies, an agreement governing the trade of weapons and technology that could be used for military purposes. Originally intended to prevent proliferation and build-up of weapons, the US and other Western nations pushed for operating system, software, and network exploits to be included in the Wassenaar protocol to prevent the use of commercial malware and hacking tools by repressive regimes against their own people for surveillance.

These concerns appear to have been borne out by documents revealed last year in the breach of Italy-based Hacking Team, which showed the company was selling exploits to Sudan and other regimes with a record of human rights abuses. Network surveillance and "IMSI catcher" systems for intercepting phone calls had been covered in a 2011 Wassenaar rule after widespread use of the tools during the "Arab Spring" uprisings. Security systems from Blue Coat were resold to a number of repressive states through back channels, including Syria's Assad regime—which may have used the software to identify and target opposition activists.

But the framework the State Department brought back from Wassenaar contained language that "was too broad and would harm cybersecurity," Harley Geiger, director of public policy at the security and penetration testing tools vendor Rapid7, told Ars.

The initial rules proposed under new provisions negotiated by the State Department in 2013—which arose from trade restrictions introduced initially by France and the United Kingdom—were intended to prevent "bad" countries from obtaining technology like network surveillance tools and spyware. But the language would have placed export licensing controls on a broad range of technology, software, and services related to legitimate computer security, including systems specifically designed to block malware, penetration testing tools, and possibly even security training.

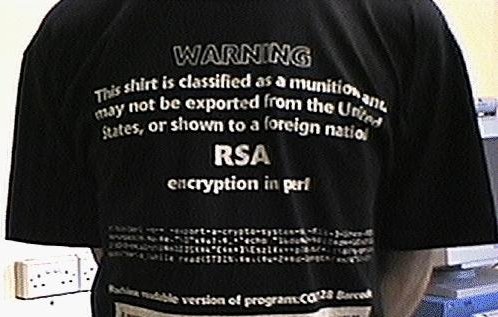

The same sort of rules once restricted the export of commercial-grade encryption, placing it under International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR). The perl code for RSA encryption was famously printed on a t-shirt in protest of its classification as an "ITAR controlled munition."

The implementation that Commerce proposed, Geiger explained, may have prevented companies from sharing information about potential exploits with overseas subsidiaries. Companies that provide penetration testing services, such as Rapid7, would run into difficulty providing those services overseas. "The number of licenses you would have to apply for normal cybersecurity operations would multiply greatly," Geiger said.

Normally, US regulations implementing Wassenaar protocols are simply issued. But the Commerce Department's Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) took the unusual step of opening proposed exploit rules up for public comment. The immediate feedback to the first set of rules proposed was almost universally negative. The rules' language is flawed partially because of the broad interpretation of what "intrusion" technology is. The regulations proposed swept up defensive software systems as well because they include information about exploits.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, the Center for Democracy and Technology, and Human Rights Watch joined in submitting comments about the proposed rules. The groups warned that the rules were overly broad—they placed restrictions on cybersecurity software, for example, because the software "may incorporate encryption functionality."

Rapid7's team commented that the proposed rules would "establish controls on 'technology required for the development of 'intrusion software,' which would regulate exports, re-exports and transfers of technical information required for developing, testing, refining, and evaluating exploits and other forms of software meeting the proposed definition of 'intrusion software.' This is the type of information and technology that would be exchanged by security researchers, or conveyed to a software developer or public reporting organization when reporting an exploit." The rule, they argued, would have a chilling effect on security research.

The outcry led to congressional hearings on the proposed rules' impact, which led to the inter-agency panel's reconsidering of the rules. "Today’s announcement represents a major victory for cybersecurity here and around the world,” said Rep. Jim Langevin (D-R.I.), who led the Congressional effort to stop the proposed rules, in a statement issued on Tuesday on the conclusions of that panel to renegotiate. "While well-intentioned, the Wassenaar Arrangement’s ‘intrusion software’ control was imprecisely drafted, and it has become evident that there is simply no way to interpret the plain language of the text in a way that does not sweep up a multitude of important security products."

The EFF was similarly enthusiastic about the decision, posting news of the shift under the headline, "Victory!" But while optimistic, Geiger—who joined Rapid7 from the Center for Democracy and Technology in January—remains cautious about how much will be renegotiated. The agreements cover intrusion "technology, software and systems" as separate categories, and the wording of the decision he had seen didn't indicate if all three would be addressed—or if only "technology" (hardware) would be. "These controls should be removed completely to enable legit cybersecurity activity," Geiger said. "But if it's not possible, we think the reforms should be comprehensive and not just include technology but also software and systems and change the definition of intrusion software."

reader comments

33